Risk management versus "people

Business Psychology Research findings over the past decades indicate that risk management activities are susceptible to cognitive and group biases. Decision makers overestimate some risks and underestimate, if not overlook, others. Which of these biases do risk managers and decision makers need to understand? And how can they be effectively reduced in practice?

The identification and assessment of risks are two important sub-processes that all persons entrusted with risk management in companies deal with. Based on this, they can make recommendations to management as to whether one or more risks lie within the tolerance limits and how to react in order to reduce the probability of occurrence and/or the potential damage to an acceptable level.

However, there are considerable "cognitive stumbling blocks" in the individual process steps, such as obvious threats that do not receive the necessary attention (e.g. danger from cyberattacks, dependence on oil and electricity suppliers). Instead, a lot of energy is often put into identifying and assessing 'black swans', which by definition are not predictable (cf. Wu cker, 2018). This apparent contradiction cannot be explained rationally, but rather lies in the way people perceive risks.

Distorted scenarios

In addition to all the technical know-how, one thing is certain: a modern risk manager must be able to understand why people (over)react to some risks while ignoring others that are objectively more important. Understanding and influencing this human behavior is usually more critical to effective risk management than applying advanced valuation methods. When making critical risk assessments, decision makers often rely on a combination of data, knowledge and experience. Whether consciously or not, the brain relies on unconscious psychological biases. In human development, these have served as a protective mechanism and have become essential for survival. In today's complex world, such biases, if not actively managed, can themselves become a risk for companies.

If risks appear to be more or less true than they actually are, this can be an indication of cognitive biases. The latter influence risk assessment and thus have a significant impact on the creation and assessment of risk scenarios in companies. In turn, biased scenarios can lead decision makers to make suboptimal or even fatal decisions under uncertainty. The number of cognitive and group-specific risk scenarios known to date has increased considerably.

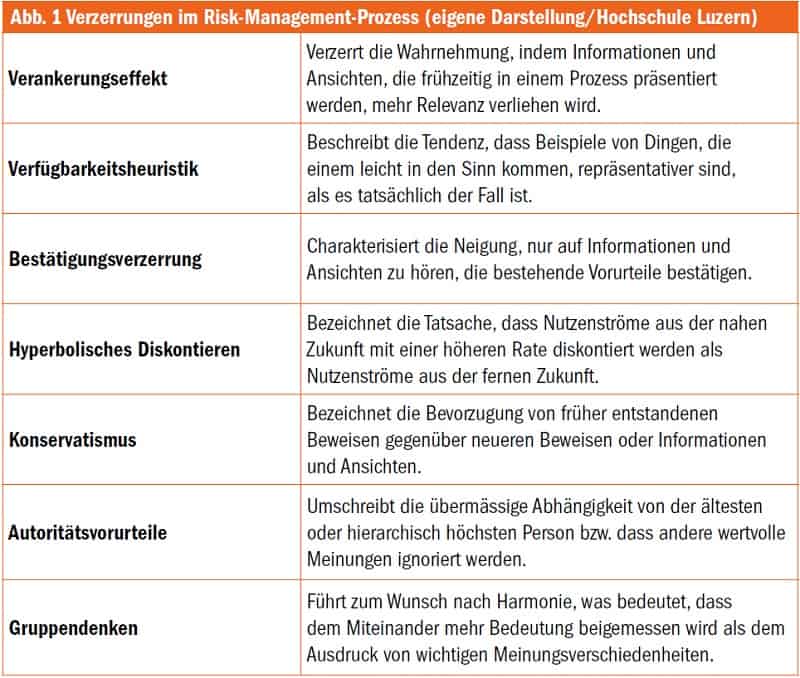

bias effects is huge - depending on the source, it is well over 100 (cf. e.g. Shefrin, 2016). A significant proportion of these also play an important role in the risk management process. Often, however, little attention is paid in practice to whether many of these effects are known. Figure 1 summarizes some of the key distorting effects from the authors' point of view.

Different strategies

One of the most widespread cognitive biases is the availability heuristic. In the context of risk identification, this means that decision makers focus on obvious risks that come to mind first. If participants in risk workshops have had recent experience with a risk, these risks are more present (available) than others and are therefore often classified as more relevant. In addition, the media presence of certain emotionally significant events can have a major influence on risk selection and distract from unspectacular events with high loss potential.

Hyperbolic discounting works in situations where decision-makers have to choose between short-term benefits and long-term goals. Incentives such as quarterly reporting often lead to prioritizing short-term financial figures (cf. Wu cker, 2018). As a result, pending decisions are postponed or sensible investments that affect financial performance in the short term are not made. There is also a risk that important risk management measures, which tie up resources and only have an effect in the long term, will be postponed.

Special mention should be made of group situations such as management meetings, in which anchoring effects and prejudices of authority can have a significant influence on the views of members. Cultural differences in group composition also play a decisive role in such situations. On the one hand, it is conceivable that one's own convictions of wanting consensus are adapted to the chairperson, or on the other hand that more weight is given to information presented early on (cf. Montibeller & von Winterfeldt, 2015).

The question now arises as to how such distortions can be reduced in practice. Various strategies exist for this purpose, which are more or less promising depending on the corporate culture in which they are practiced. From a generic point of view, the steps listed in Figure 2 represent initial measures for more distortion-free, risk-based decisions. In this respect, it seems important to follow the strategies even under "hot" emotional conditions, i.e. in a turbulent environment or in situations under time pressure.

In order to prevent the aforementioned distortions of group thinking, it is important to take account of contextual factors and adapt the processes accordingly. For example, the diversity of a committee promotes structured debates and constructive differences of opinion. The size of five to eight participants prevents hiding in the group and allows all members to express their opinions before an evaluation and selection is made.

make decisions

Anonymous opinion polls at the beginning of group meetings also help to generate more truthful views about risks. The collected input enables decision-making that is less influenced by the aforementioned biases (cf. Montibeller & von Winterfeldt, 2015). Finally, in order to prevent conformity in the group, it may be useful to designate a group member who, in the sense of a critical counterweight, questions all decisions in an objectively justified manner.

Technological advances, the resulting data and improved analysis methods allow for an expanded risk analysis. This includes, for example, the improved identification of trends, a more precise risk assessment and the establishment of a comprehensive early warning system (cf. Romei ke, 2017). However, this does not make the decision-making process of companies more objective per se, because the decision-maker is ultimately still equally susceptible to distortions, irrespective of the method used.

Objective solution finding

This is because the underlying models are created by humans themselves. In addition, the interpretation of the data on which critical risk decisions are based is subject to numerous potential biases (e.g. confirmation bias or con servatism). Finally, risk data are often of poor quality, which is why people play a central role in their selection and preparation.

The question is not whether psycho logical distortions* exist in risk management, but how they can be identified and effectively reduced. The concrete identification and understanding of the human risk factor is of decisive importance here. Only when the individual decision-makers themselves recognize the distortions does it become clear where a company is at risk. With this knowledge, effective measures can then be implemented to reduce the distortions in order to prevent crises or at least reduce the damage caused by them.