On the standardization of the blockchain

The distribution of digital assets via interconnected computers seems to simplify, if not improve, transactions in the area of efficiency in the IT, FinTech, but also government and healthcare sectors and many other businesses. Nevertheless, the promising yet complex blockchain technology has yet to be standardized.

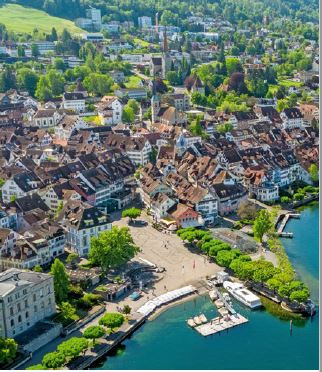

Just a few years ago, blockchain technology was promised to bring about a new revolution, while at the same time improving financial transactions and business processes. Individual regions, such as the "Crypto Valley" proclaimed by the Zug government, have attracted a number of start-up companies. Possibly because the Zug government equates values such as collaboration, integrity, security and transparency with Bitcoins.

Nonetheless, cryptocurrency providers have been infiltrated by cybercriminal organizations time and again. A digital technology that is used by companies and private users alike should have a uniform standard at the very least. The Swiss financial centre in particular must be able to protect itself from ominous access by hackers and programmers.

The cryptographically secured concatenation of individual information blocks therefore not only holds promising cooperative opportunities, but also risky effects.

Swiss Standards Committee

Meanwhile, in this country, organizations such as the Swiss standards committee INB/NK208 ("Blockchain and distributed ledger technologies") are also concerned about the standardization of previously peripherally distributed blockchains. The inaugural meeting of ISO TC 307 "Blockchain and distributed ledger technologies (DLT)", held in Sydney, Australia in 2018, brought together international experts from over 30 countries to set the course for future standardization in this area.

Five study groups were formed for standard development in the following areas:

- SG1 "Reference architecture, taxonomy and ontology"

- SG2 "Use cases

- SG3 "Security and privacy

- SG4 "Identity"

- SG5 "Smart contracts

Not only has the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) defined important points regarding blockchain, but Switzerland is also working on standardization. For example, Thomas Puschmann is also dealing with important points regarding "Blockchain and distributed ledger technologies" in a committee for Blockchain.

Puschmann, a researcher at the Swiss Fin- Tech Innovation Lab at the University of Zurich, is chairman of the Swiss Standards Committee INB/NK208. This committee revolves around future standardisation work. However, in order to be able to standardise the blockchain, you first have to understand it properly.

"A blockchain records all the transactions of all the players involved and publishes them publicly," the expert tells Management & Quality. "In this way, all transactions of all involved actors are transparent at all times. In principle, decentrally organized systems such as blockchain do not require any intermediaries to process transactions, as authentication as well as transaction processing take place via the blockchain. A key element is therefore the security of the blockchain solution."

By stringing all the blocks together, it is possible to trace and verify every past transaction back to the first block, called the Genesis Block.

Unlike an IPO (Initial Public Offering), in which a company issues securities on a stock exchange, a purely digital transaction through an ICO (Initial Coin Offering) takes place on the internet. The blockchain expert and author further explains: "The process, which takes place without intermediaries, and the type of 'securities', which are typically distributed in the form of digital tokens, are also different.

The legal modus operandi

One of the most important direct effects of blockchain is the "avoidance" of intermediaries such as clearing institutions.

Per se, a blockchain transaction is subject to a so-called smart contract, an electronically mapped contract "that can be compared to an insurance contract or a service contract", which contains economically and legally binding rules, "is electronically readable and thus contains automatable building blocks", says the expert.

Basically, any smart contract could be implemented on a blockchain, or DLT, and thus "obey" the same basic principles as transcation-oriented blockchains. Puschmann makes a comparison using an example: "If a vehicle owner has not paid his insurance on time, his leasing contract could then be blocked and a driving ban could be automatically issued at the responsible road traffic office"; analogously, according to the standards expert, lacking or unfair blockchain transcations could be "blocked" by network blocks.

Another effect of those smart contracts is a parallel digitalization of legal and economic rules. Thomas Puschmann says: "In this way, this technology fills a gap that has existed until now, in that it now also includes the area of values in addition to the standardization of information access (HTML, codes, etc.) and actual service access (SOAP, etc.). »

In addition, this technology makes it possible for the first time to securely transfer values (money, securities, etc.) of any kind electronically.

Risks and consequences

The consequences of blockchain technologies for Swiss sectors are still uncertain. The Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) has published initial guidelines for ICOs (Initial Coin Offering). In doing so, it is primarily addressing the issues of money laundering and trading in investments. Concrete regulatory elements in the taxation of individual users or traders have not yet been defined across all Swiss authorities.

Until now, providers that produce virtual currencies or act as payment service providers have been subject to the usual FINMA regulations.

However: A Bitcoin unfortunately still does not represent a right to the delivery of a good or the provision of a service. Thus, there is also no repayment obligation or an actual right to a share of the profits should the Bitcoin price "go through the roof" again. Basically, a cryptocurrency does not contain any consumption value. From a tax perspective, a cryptocurrency is considered a type of digital money. The tax authorities then also treat a blockchain value like a foreign currency, communicating a year-end rate for larger transactions (currently). Demian Stauber, a member of the Swiss standards committee "Blockchain ISO TC 307" and lawyer for intellectual property law, information technology law and contract law, points out:

"The blockchain issues that FINMA has put on the agenda only mark a discussion. Some classification approaches are still needed to typify the new technology. So it's not just about the technical architecture layer (e.g. applications, logging), it's ultimately about the lifecycle of a token (for creation, sale, brokerage, distribution, etc.)."

Such points (see infobox) lead to more far-reaching regulatory and legal issues that are not currently the subject of discussion.