Knowledge management in the digital age

How do we ensure that the (experience) knowledge of employees and work teams is constantly passed on across departments? Many companies are currently asking themselves this question, because in an age in which speed is an important success factor, knowledge islands in the organization are becoming an ever greater entrepreneurial risk.

For their work, companies and their employees not only need knowledge and know-how, they also gather knowledge and know-how in the process - for example, about

- how certain customers and markets tick or

- how to best solve certain tasks and problems or

- what you should pay attention to when managing projects or leading employees.

The sum of this know-how largely determines how efficient and successful a company is. It also determines how quickly and effectively it can respond to new challenges, because it has learned from past experience and drawn the necessary conclusions.

Preserving and developing knowledge

That is why the topic of knowledge management - i.e. the question of how an organization ensures that a) knowledge is not lost and b) that it is stored and documented in such a way that it can be passed on to all employees who need it for their (future) work - also played an important role at a time when the term knowledge management did not yet exist. Even then, for example, traders or farmers were already asking themselves: How do we pass on to our descendants the knowledge that has accumulated in our heads over the years? And specialists such as craftsmen asked themselves: How do we pass on our expert knowledge and experience to our employees?

Although this transfer of knowledge was already taking place in a more or less structured form at that time, knowledge transfer was not yet understood as a management process that was to be designed in a systematic and goal-oriented manner. This awareness only gradually developed in the course of industrialization, when

- ever larger companies emerged, producing and selling ever more complex products, and

- the organisation of work became more and more divided, which also led to the emergence of more knowledge islands, which possessed specialised or expert knowledge that the rest of the organisation lacked in whole or in part.

In this context, the question also gained relevance: How do we ensure that the knowledge base of our organization is not only preserved, but also renewed in such a way that the company is also successful in the medium and long term?

Challenge: Transfer of experiential knowledge

Increasingly, a distinction was made between so-called "explicit" and "tacit" knowledge - two terms coined by the chemist and philosopher Michael Polanyi, among others in his 1958 book Personal Knowledge and in the 1966 book The Tacit Dimension, a revision of lectures he gave as a professor at Aberdeen University in the USA after his retirement in 1959.

As a rule, the term "explicit knowledge" subsumes knowledge that can be clearly codified and documented and passed on to other persons by means of language, writing, drawings and pictures, among other things. This is largely rule and factual knowledge that can be passed on to other people, for example in the form of reports, textbooks/manuals, work instructions, written procedures/organizational charts or drawings. This also includes all scientific knowledge that is based on figures, data and facts and is communicated via publications in a formalised language. Due to its coded form, this explicit knowledge can be stored, processed and transferred on numerous media.

The term "tacit knowledge", on the other hand, refers to knowledge that is often referred to as experiential knowledge. This knowledge, which is fed by experiences, memories and convictions, refers to the skills of a person or organisation. It can be conscious to its bearer, but it does not have to be. In any case, however, it cannot be codified and documented, or only with difficulty, and can thus be passed on to other persons and organisations. Typical examples of tacit knowledge in an operational context are,

- when an experienced salesperson intuitively senses how to behave tactically and strategically with certain customers in order to win an order; or

- when an experienced technician knows that if certain maintenance work is not done soon on a machine, the company will have problems with it without being able to justify it; or

- When an entrepreneur or manager is told by his gut feeling, even though all the facts seem to speak against it, the company should take advantage of this opportunity in order to be successful in the long term.

Implicit knowledge is linked to attitudes

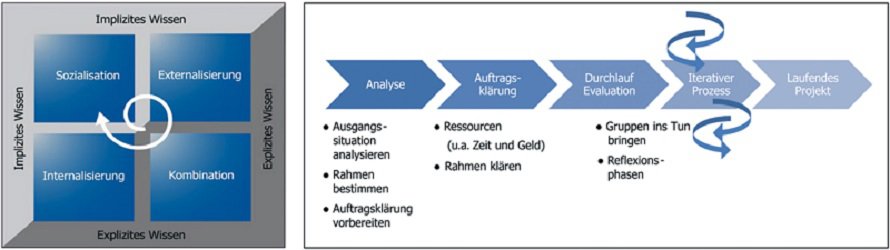

Both forms of knowledge (Figure 1) are important for the success of a company, whereby it is generally the case that it is easier for companies to impart explicit knowledge - not only because it can be documented, but also because they have already gained a great deal of experience in this area in their training and further education departments.

The situation is different with tacit knowledge. Imparting it often requires that it first be transformed into explicit knowledge in a targeted process of externalization - for example, through a systematic survey of the knowledge bearers or a systematic analysis of their actions - so that it can be documented. However, this externalisation (Figure 2) is often only possible to a limited extent in the case of tacit knowledge, which is why it can often only be passed on to other people in dialogue-based processes such as coaching and mentoring programmes.

In addition, there is implicit knowledge: It is often linked not only to concrete experiences but also to attitudes, convictions and attitudes that are partly brought about by them. For this reason, it is not uncommon for people who wish to internalise this knowledge - i.e. acquire it in such a way that it becomes an integral part of their skills - to also require a change in attitude and behaviour. Otherwise it has no effect. This is another reason why it can often only be passed on in dialogical processes.

Complexity requires different knowledge management

A rule of thumb can be applied here: The more complex a task is, the more tacit knowledge must be transferred to solve it. This is relevant insofar as in recent years, among other things in the course of the globalization of the economy as well as its advancing digitalization, the working world - at least in the perception of the employees - has become increasingly complex. Therefore, it is not a risky proposition: companies must attach greater importance to the transfer of tacit knowledge and thus also allocate time and resources if they want to avoid the emergence of more and more islands of knowledge in their organization, which would ultimately be

- complicate the often desired cross-hierarchical and cross-departmental, not infrequently even cross-company team and project work,

- stand in the way of creating the necessary structures to react quickly and flexibly or agilely to new challenges, and

- prevent an increase in the innovative power and speed of the organisation.

In addition to this challenge, companies are confronted with another one in the area of knowledge management: Explicit knowledge, which was often passed on from generation to generation in the past, is also rapidly becoming obsolete in the VUKA world, which is characterized by rapid change and decreasing predictability, as well as in the age of the digital transformation of the economy and society. The same applies to externalized implicit knowledge: Old recipes for success are often no longer suitable or must be regularly put to the test due to the changed framework conditions. It is true that explicit knowledge can be updated and disseminated throughout the organization much more easily today than in the past, since it is often stored electronically (for example, in internal company wikis); nevertheless, companies are faced with the challenge of continually updating it. Therefore, the old adage is more true than ever: knowledge management is an ongoing project (or process). It has a beginning, but no end.

Knowledge management becomes an ongoing project

Many companies have recognized this in recent years. Therefore, they are rethinking their traditional knowledge management and are increasingly trying to adapt it to the framework conditions and requirements of the digital age. This process usually proceeds as follows: In a first step, as in almost all projects, the actual or initial situation is analyzed. Questions are asked such as:

- How is our knowledge management done today?

- Does this still meet the requirements of the digital age?

- Can our corporate goals, such as reacting faster and more flexibly to market changes, still be achieved in this way?

- Where is there a need for change? Based on this, questions arise that are related to the clarification of the order, such as:

- Which knowledge do we need (in the future) due to its relevance to success and should therefore be continuously expanded?

- Is this explicit and/or tacit knowledge? -- Who are the relevant knowledge carriers?

Once these questions have been provisionally clarified, questions arise such as: What resources (including time, money, technologies, procedures) are available to us for knowledge identification, knowledge documentation and distribution, and knowledge development, and what resources do we need? What framework conditions of a structural, cultural and motivational nature do we need so that our organization does not become a bureaucratic knowledge administration, but a goal-oriented knowledge market that transcends hierarchies, departments and functions?

Maintain agility in knowledge management as well

Once these questions have been provisionally clarified, the first trial balloons can be launched in order to gradually adapt knowledge management to the requirements of the digital age. It is important that this happens in an iterative process in which reflection loops are repeatedly built in, such as: "Are we still on the right track?", since the companies or project teams are entering new territory here - not only because modern information and communication technology provides them with new possibilities for knowledge identification, storage and documentation as well as knowledge dissemination.

It is at least as relevant to check regularly during the course of the process or project:

- Do we even collect the knowledge relevant to success that our organization needs (in the future) in the path we have chosen?

- Have we won over the relevant knowledge bearers as comrades-in-arms in the attempt to create a fluid knowledge market in the organisation?

- Does the collected knowledge reach the employees who need it for their work and is it used effectively by them?

These questions must be asked again and again during the course of the project in order to achieve the overriding goal. This is to make the company fit for the future.

Fluid knowledge market needs strong promoters

This is currently often made more difficult by the fact that a related goal is often: The company should be able to react faster and more agile to new challenges. For this reason, many companies are currently creating structures - especially in the areas in which the core services of the organization are provided - that are intended to enable the individual work teams to work more autonomously and in a self-determined manner. However, this always carries the risk of creating knowledge islands in the organization once again.

Therefore, knowledge managers are actually always faced with the challenge in their practical work,

- on the one hand, to create the structures and framework conditions that are necessary for modern, future-oriented knowledge management, which also requires a certain alignment - i.e. an agreement on common goals and a binding approach and behaviour, and

- on the other hand, not to create a bureaucratic juggernaut, which in turn makes agile working more difficult

Finding the necessary balance here is not only a complex management task, but also a leadership task, because this requires that all those involved

- to create an awareness why a modern, future-oriented knowledge management is necessary for the success of the company, as well as

- Promote the mindset necessary for a fluid knowledge market to emerge in the organization (Figure 3).

Without strong promoters at all management and leadership levels, this will not succeed.