Measuring organizational resilience

The ability of an organization to successfully deal with adversity and setbacks is referred to as its resilience. However, the concept is relatively abstract. A measurement of organisational resilience provides a remedy. Through a benchmark, it becomes possible to discuss practical consequences and systematically improve corporate fitness.

At the individual level, resilience means the ability to improve emotional regulation and impulse control, deepen root cause analysis, believe in self-efficacy, and cultivate and build empathy and individual networks. Organizational resilience is a broader system resilience and includes self-organized learning to adapt the system, commonly in terms of diversity, creativity, robustness, early detection, as well as persistence. Arguably, a resilient organization needs both: a resilient system and appropriately equipped individuals. While psychological tools can be used at the individual level, there are far fewer tools available at the organisational level.

Capturing organisational resilience

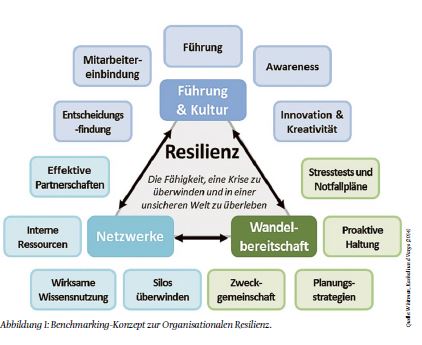

Although organisational resilience is difficult to measure and grasp, there are practical consequences if a resilience perspective is applied to the company: ISO standard 22316, which describes the basic terms and methods, is a suitable management approach. Organisational resilience is dealt with here on the basis of nine topics and provided with guidance on systematic management. Unfortunately, the standard remains far too superficial as a concrete management tool. The authors of the standard included New Zealand researchers who, at the University of Auckland, presented the first sufficiently comprehensive concept for organisational resilience around ten years ago. They did so against the background of crisis response and prevention in New Zealand's natural disasters, as earthquakes in particular had hit the regional economy several times. The concept is based on the three corner components "Leadership & Culture", "Change Readiness" and "Networks" (see figure below). The corresponding sub-topics per component are very different and pragmatically composed, e.g. "Employee Involvement", "Awareness" (situational awareness), "Stress Tests and Emergency Plans" or even "Overcoming Silos " and "Effective Use of Knowledge".

Whitman and colleagues intentionally draw the interpretive framework very broadly here to show the extent to which resilience is to be understood as a system function that influences any subtopic of organizations and their management.

Tools for managing organisational resilience

The authors also developed a first benchmarking tool for the model: The "BRT 53" comprises quantifying questionnaires with about 80 question items. This means that the answers to the categories can now be summarized and compared in larger groups. The authors have extensive survey data for different organizational sizes that can be used for such a benchmarking of resilience competence.

If this survey is carried out among all decision-makers in the organisation, an overall picture is obtained which can be used for further strategic management of the organisation.

Another instrument for measurement that is even more strongly related to corporate management would be the "Resilience Check" by Seidenschwarz/ Pedell (2011). Here, guiding questions are formulated, but not constructed as a benchmark.

The two concepts thus offer a comprehensive catalogue of questions for recording resilience-relevant aspects in companies. They highlight the importance of multiple environmental factors that can lead to critical situations. However, neither of the concepts would reject a robust approach to crisis management, but they are not sufficient on their own. The resilience benchmark is conspicuous for a certain pragmatic superficiality. There is a risk of theoretical truncation here, as the papers on high reliability and security management are largely based on a deeper understanding of organisational psychology. This should always be taken into account when interpreting evaluations.

An adapted model for Swiss companies

Until now, there has been no specific model for Swiss or German-speaking companies. The Resilience Check is not sufficiently operationalized and the BRT-53 benchmark is too extensive and, moreover, not entirely easy to apply due to the English language. At the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts it was translated and significantly shortened. An application can now be carried out in 15 minutes per questionnaire. In addition, an Excel tool was created for evaluation. Here, the results of the respondents can be efficiently combined. As a result, the results are displayed in a spider diagram. The comprehensive overview shows where the resilience profile of the company contains weaknesses.

An example illustrates this analytical capability. For reasons of confidentiality, it is based on several benchmarks carried out in the service sector in companies with up to 120 employees. Here, the questionnaires were completed with the management crews as part of their management retreats, then collated, evaluated and discussed together. The spider diagram shown (see figure above) reveals two crucial details at second glance.

The spider diagram shows on a percentage scale that the area "Leadership and Culture" is rated best. In particular, situational awareness is rated positively, but also the areas of "innovation & creativity" and "decision-making ". Now, in the context of their retreats, business leaders are usually very aware that things have to be decided and that business does not run itself. This could be a bias, but still these values are very prominent. Employee engagement is rated the lowest. This is a value that makes one sit up and take notice. While 70% are not bad, everything else here is rated better. Behind this are the items on employee motivation and commitment, both of which appear to be in need of improvement from the managers' point of view.

In the area of readiness for change, far fewer high values are given. In particular, the part "stress testing of (emergency) plans" scores poorly. Why is that? Presumably every employee has experienced what an evacuation drill means. And anyone who has already participated in the evaluation of one is well aware that there can never be enough practice here. However, such exercises are time-consuming and ultimately very expensive, so that companies can never be completely up to date in this area.

Finally, in the area of "networks and partnerships", the partnerships themselves and also interdepartmental work are judged far more positively than the distribution of internal resources and knowledge transfer. Behind these two themes are sufficient finances and dependence on key people. All organisations are concerned about their liquidity and see a permanent shortage here due to dependence on key people. In the discussions it emerged that key persons were located in the governance bodies of the organisation but not in middle management. However, this is also true here: The corporate base was not consulted. They could, of course, see things differently again.

With the results, it is now possible to develop, prioritize and argue for measures in the overall picture. For example, one might want to promote employee involvement, but in order to increase resilience, one would actually first have to promote the exercise of emergency plans and work on flatter hierarchical structures, should this be desired by the owners at all.

Conclusions

It has become clear in this paper that in order to increase system resilience, at least two levels need to be considered equally: the individual and the organizational. Certain tools are available at both levels, although in the case of organisational resilience this needs to be developed further. The ISO standard is not sufficient for this purpose. System resilience can be systematically increased if the various activities of a context are modelled and analysed. This is where our model for benchmarking Swiss companies comes in handy.